Five questions for this American master of the short story.

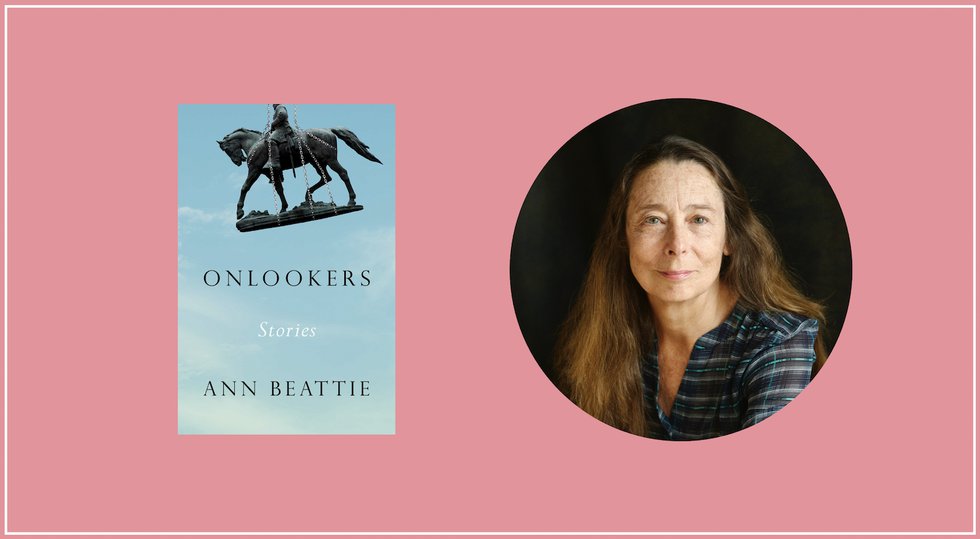

Onlookers by Ann Beattie. Scribner. pp. 288. $28.

Konstantin Rega: Where did these stories originate from?

Ann Beattie: When I started writing these stories, I had the idea that they would be based in Virginia. But at that point, I’d only written one of them. And I was thinking about putting the Lee statue in the next one. So that gave me a little seed of an idea, of the book being more about the issues around statue removal.

I start on something without having any idea of the middle and the end. And I don’t even really know the first line. 60% of everything I write gets thrown out usually. If there isn’t some artistic dynamic embodied within the story, then it doesn’t seem engaging enough. In other words, there has to be something that quickly makes me feel both comfortable with the material and uncomfortable with it—something that will soon be discovered by me as the writer.

What made you decide on the short story form?

Well, I tried poetry, and I was terrible. I still don’t like to write novels. Many writers come to mind as people who have the ability to be flexible in different forms. And I can do my best with other forms. But what seems to come naturally to me, is the short story because. For me, it has certain advantages that play to what talents I have, such as compression. I really like what the short story requires of me; I find it challenging but fun.

What do you want the reader to get from this reading experience?

I think the same thing that I always got out of it as a Charlottesville alien, that these things were very specific to the region. And of course, my attitude was enlightened and changed as to what these things meant—what they stood for. For many, they were also just part of daily life, and there was a kind of acceptance. In the same way that you might think, “Oh, this is the park that has the most flowering trees,” you might also think, “This is the park that has the young soldier.”

I didn’t want to write a disguised essay about what was the norm for a long period of time, and in many places in our nation. But I did want to make these things both part of daily life and then bring it more into the present by showing either activism or changed attitudes. They’re not conventionally linked stories. It’s not Elizabeth Strout or Frank Bascombe. The idea of just circulating through the world—and the world, in this case, happens to be Charlottesville.

You were the Edgar Allan Poe Chair of the Department of English and Creative Writing at UVA from 2000-13. When did you move to Charlottesville?

Well, it was my first job out of graduate school in 1975. It was absolutely random that I came to Virginia. I had one job offer, and it was for one year. It wasn’t tenure track or anything like that. I had not written my dissertation. And in fact, to this day, I’ve never done an advanced degree. I became successful as a freelance writer amazingly.

I grew up in Washington, D.C., which was more of a southern city when I was a little girl than the way you would typify it now. And when I went to Charlottesville, I saw it was like an improvement upon the way I had grown up. I thought that was terrific. And I must say in those days, the university was so different. For whatever reason, it really was very welcoming, and even kind of inspirational to be there with my colleagues. I had older people taking a great interest in me. Peter Taylor was certainly one of them, who took me under his wing right away, and that was really lovely for me. I just felt included. And I made very good friends; some who are still my closest friends were hired the same year I was.

What other collection of stories would you recommend to someone?

I would really recommend Rock Springs by Richard Ford, his early collection. My favorite story in the whole book is the title story. It’s an assortment of stories based in the West. I think he’s very moving as a writer of short stories. And he’s so subtle, such a good stylist, that you look at the note on which he ends and you think, wow, I would never have thought we would have gotten there in a million years. But in retrospect, that makes perfect sense, that’s really eloquent—or whatever approving word you want to put on it. He has a voice like no one else.

Get a copy at The Bookshop.