After 60 years in the forefront of rhythm and blues, soul, gospel and rock, tenor saxophone legend and Norfolk native Gene Barge keeps the music movin’ and groovin’.

A Nite With Daddy G

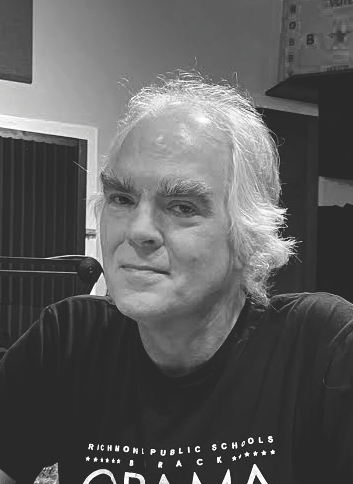

Gene Barge

Gene Barge

Vinyl copy of “A Nite With Daddy G (Part Two).”

CD re-issue of “The Very Best of Jimmy Soul”

CD re-issue of “The Norfolk VA. Rock ‘n’ Roll Sound”

CD re-issue of “U.S. Bonds Meets Daddy G”

CD re-issue of “Dance With Daddy ‘G’”

Newspaper ad for the 1958 Tidewater Jazz Festival, featuring The Gene Barge Jazz Quintet.

“Daddy G” is born: Gene Barge’s rollicking tribute to Bishop Daddy Grace charts on WGH, Jan. 15, 1961. The instrumental would later serve as the music for Gary U.S. Bonds’ #1 pop smash, “Quarter to Three.”

Barge (seated second from left) on the panel of Frankie’s Jazz Workshop in 1958. The television show on Norfolk’s WTOV was hosted and sponsored by future “Norfolk Sound” producer Frank Guida, at right.

“I played behind James Brown here when he was first coming out,” Gene Barge recalls with a smile. “He didn’t even have a band. And I played behind Little Richard, too. This was in the ’50s.”

The game is called “Six Degrees of Separation from Gene Barge.” Throw out a name and chances are you will find a connection to the lean, frosty-haired saxophonist relaxing in his Virginia Beach hotel room, waiting for yet another gig to start. In a prolific career that roughly parallels the development in African American popular music from R&B to soul and funk to rap, the Norfolk native nicknamed Daddy G has played with, arranged, produced and/or written songs for a dizzying array of performers, including Chuck Willis, Bo Diddley, Muddy Waters, Jackie Wilson, the Rolling Stones, Natalie Cole, Johnny Winter, the Chi-Lites, even Public Enemy.

But the parlor game doesn’t end there. If you recognize his distinctive face—handsome and alert but comfortably worn in—it’s probably not from his 60-year career in music. Barge added “Hollywood Character Actor” to his resume late in life. He’s appeared on the big screen with stars such as Gene Hackman, Harrison Ford and Kevin Costner in films like The Fugitive, Under Siege and last year’s The Guardian.

The 80-year-old musician honed his entertainment skills here at the Beach, a half-century ago, in long-gone area dives. “[Back then], we’d play a place and they only had one microphone for the whole band. It was tough. The sax players had to have iron lungs, man.”

In the early ’60s, Barge became internationally known as “Daddy G” and was a catalyst for what would become known as “The Norfolk Sound” that spawned numerous Top 10 hits for singers Gary U.S. Bonds and Jimmy Soul—influential songs cut in a downtown Norfolk studio by regional musicians. Barge himself co-wrote many of the biggest, including a 1961 #1 pop hit “Quarter to Three,” now considered a pivotal song in rock ‘n’ roll history.

“Norfolk didn’t produce a lot of the musicians in the mainstream of rhythm and blues because of the economics here,” he says. “They couldn’t make a living here. A lot of the musicians left town before I got the chance to even know them good.”

He himself bolted for Chicago in 1964 to work for Chess Records, America’s premier blues label. It wasn’t long before he was playing on another smash, “Rescue Me,” by Fontella Bass, and convincing the company to take a chance on an up-and-coming blues guitarist named Buddy Guy. “I talked to Buddy the other day,” Barge says. “I might be working with him on his next album, doing production.”

Daddy G would stay in Chicago even after Chess went under, producing, arranging and playing sessions, even winning a Grammy for his work with Natalie Cole and touring with the Stones. Since the 1980s, the easy-going hornman has been one of the forces behind the hard-gigging Chicago Rhythm & Blues Kings. At a time when many men his age are retired or hardly functioning, he plays more than 100 dates a year—vital, and still in the game. He recently found out that Jay-Z had sampled one of his earlier records. When Martin Scorsese needed assistance with his PBS documentary, 2003’s The Blues, one of the key people he consulted was Barge.

“The history of rhythm and blues in the 1950s and soul in the 1960s and 1970s is largely a history of sax players,” writes U.K. music journalist Barry Cornell. “Time has come when one of the most versatile tenor players of this period needs serious re-revaluation. His name is Gene Barge.”

It began in 1946, with a battered horn.

“My daddy was a welder in the Norfolk Navy Yard, which was located in Portsmouth, of all places,” Daddy G recalls with a chuckle. “He was working on ships involved in the war out in the Atlantic Ocean, and they’d drag them in for repair. This particular ship was a British ship that had been torpedoed. The sailors had sealed off a particular section of the ship to keep it from sinking, and in this sealed-off section there was a lot of stuff, including a saxophone. So a British sailor gave it to my dad, but it was water-soaked. So I took it to a friend of mine, Leroy Catfay, who was a good saxophone player, and he said, ‘We’ll see what we can do.’ We finally found a guy, an old Navy chief that fixed instruments. We got that sax and tried to clean it up, put new pads on it, and that’s what I started on.”

It came to the 20-year-old Barge at a pivotal time. The thin, somewhat shy young man had just completed a two-year stint in the Air Force—“I was trying to be a pilot, but the war was winding down”—and was preparing to enroll in West Virginia State College in Charleston, as an architecture major. Born in Norfolk on August 9, 1926, James Gene Barge was the oldest of nine kids—five brothers and three half-sisters. Booker T. Washington High School is where he first developed an interest in music. “Booker T.’s band had been dormant,” he says. “When they asked for students to join the band, I had this drum that I got from my dad. But I didn’t want to play the drum. So I picked up the clarinet. It was a loaner and I remember my dad got so mad—‘You traded your drum?’”

He sang (“Booker T. had a killer choir”) and played clarinet in the band, but he never took music seriously until he found the sax. Why was he drawn to the instrument? “The saxophone was the instrument, coming up, that had the sound closest to the human voice,” he says. “It was the one with the impact. It was the featured instrument in the band, so that was the one you wanted to play.”

He switched his major to music, obsessed with practicing scales. “I couldn’t get enough of it. Once I had it, I was gone.” At Charleston, he became proficient enough to become the lead soloist of a 20-piece jazz band. His early inspiration? “I was in love with Lester Young, the saxophonist with Basie,” he says.

When the young man returned home to Norfolk in 1951, he was seasoned enough to join veteran Clint Turner’s band; after a time, he was recruited into the area’s top R&B group, the Griffin Brothers, an energetic combo enjoying national hits on the Dot label. “They knew me from way back, you know. They just needed a sax player. Earl [Swanson] was their regular guy, and he was somewhere—I don’t know where he was, but he came back.” Barge and fellow sax man Swanson would take turns in the spotlight later in the decade, alternating work for Gary U.S. Bonds.

“I played with the Five Keys, too, from Newport News,” Barge remembers, smiling. “I knew all those guys.” He developed a reputation as a dependable live pickup musician, which is how he hooked up with traveling national acts in the mid-’50s. “It was a matter of economics then. The agencies thought they weren’t making enough money to carry a band, so they’d get a pickup band. They’d say, ‘We got so-and-so in this area, so you’ll play with him.’”

He also played the smaller shothouses, with his Gene Barge Jazz Quintet. “There was a disc jockey at [radio station] WRAP that everybody loved, Jack Holmes. He opened up a joint called Jack’s Barn. We played there. Then I used to play at a place down here on Virginia Beach called Garrett’s—a little club in a small house. It was way out in the woods. Stayed open almost all night.”

One night, at another out-of-the-way spot, the Cedar Grove supper club, he began improvising the song that would become his first record. Thanks to a phone call from another DJ, Bill Curtis, “Country” would eventually be released on the Checker label by Chicago’s Chess Records in 1955, recorded at WRAP. “When Chess heard it, they said, ‘What the hell is that? Is that a saxophone?’” says Barge. “They had never heard a saxophone sound like that before.” They even gave it a word: It sounded like ‘funk.’ “That was the reputation that I got—that Gene Barge could play ‘funky.’”

“Country” made the lower rung of the R&B charts. “They wore it out locally,” he remembers of the disc. “It got to be real popular. It did pretty well up and down on the East Coast. And it got me a deal with the Shaw Agency. They booked some of the top R&B acts of the time, including Ray Charles and a Philadelphia group called the Turbans. My touring act was the Turbans.” He recalls those huge, star-filled package tours: “They would originate these shows out of New York and put about 10 top R&B acts on them: B.B. King, Ray Charles, Mickey & Sylvia. Those big R&B tours would always start in Richmond or Norfolk, that was the kickoff. They’d use the Municipal Auditorium at 9th and Granby, and then they’d go all around the South.”

While he admired Ray Charles’ music, he didn’t think much of him while on tour. “He would talk a lot of trash … when you could get him around. But Ray Charles in my day was too busy getting high.”

In 1957, Barge would make the big time, and music history, by playing a memorable solo on one of Atlantic Records’ most beloved hits—“C.C. Rider,” by Chuck Willis. The backstory behind the session is almost as dramatic as the song: “Chuck was playing in Newport News and needed a saxophone player. So one of the players in his band—he found my house, man, knocked on my door. Chuck’s sax player had either quit or was fired. So I joined the band [on its tour].

“One night [in New Jersey] Chuck says, ‘Hey, man you know what—I wanna do this tune. Why don’t you ride in the car with me after the show.’ I just got in the band, I was riding with the band, you know. But we [rode] together and he started singing ‘C.C. Rider,’ and he said, ‘Do you remember this tune?’ I said, ‘Oh yeah, I remember “C.C. Rider” all right.’ So we started singing, having a good time in the car going down the turnpike. We finally got into New York … and he said, ‘I’m going to book a demo session—would you come down with me?’ So he had the bass player, the drummer and myself. The drummer didn’t have no drums, he just had a bar stool and was beating on a magazine or something. Despite all this… the demo sounded good.

“I went on home and he gave the demo to Jerry Wexler and Ahmet Ertegun [at Atlantic Records], and they decided to record it. Chuck said, ‘I’d hate to do this without having Gene Barge.’ So he called me and said, ‘Hey, I want you on this session and I told them I want you.’ But they didn’t want to do it. Why fly a guy to New York, put him in a hotel and pay him for the session when they had plenty of saxophone players in New York? And they didn’t know me anyway. But he insisted. [So] they flew me to New York.”

At first, the trip looked to be a bust. “It was a big session. I carried my horn [and I saw that] Sam ‘the Man’ Taylor was on sax. And then Ertegun and Wexler told me they were going to pay me but they didn’t want me to play. They had everybody, you know. Chuck was standing there frowned up because he wanted me to play, but he went along with it.”

He laughs and shrugs. “I went down to the liquor store, man, got me a pint and sat down on the floor to listen to ‘em. They did 27 takes and weren’t satisfied. So Chuck said, ‘Look, why don’t you just let Gene run down one to get the feel.’ So I ran down one and they said, ‘Hold on, that’s it, you got it. Let’s cut it.’ So they sat Sam down … and two or three takes later, man, we had cut the song.”

And what a song—a mid-tempo grinder with Barge’s lazy melodies and Willis’ vocal performing an energetic, playful duet. “The riff that I was providing set the mood and tone for the song, providing an ambiance for the music,” he explains. “The guitarist and the keyboard player could feel it, and they started to hone their directions toward what I was doing.”

It became a smash hit and much-beloved golden oldie. “But I was only on one more session for them. They flew me in for it, and they didn’t want to do that either … . That was ‘Betty and Dupree.’”

He would cross paths with Atlantic again. First, Gene Barge had to deal with a live wire named Frank Guida.

“When ‘Quarter to Three’ came out, they all had to change,” Frank Guida has said. “I mean, we stood the world on its heels. There was nothing like it, nothing.”

In 1953, Guida—a self-styled “Latin from Manhattan”—bought a rundown record store at 817 Church St. in the black section of downtown Norfolk. The Bronx native picked the right time and place to start his business. Not only was there a vibrant music scene in Norfolk throughout the ’50s and ’60s, with plenty of black and white teenagers buying R&B and rock ‘n’ roll discs, but the tireless, in-your-face owner of the Frankie’s Birdland record shop knew the city’s music scene held even greater possibilities.

“Frankie’s Birdland was a means to an end,” Guida said in a rare 2000 interview (he declined to speak for this article). “I really wanted to learn the intricacies of record distribution. My major goal was always to produce records. I was a calypso singer, you know.” After hours, Guida would issue self-produced platters by local performers, the Sheiks, the Bluebeards and Andy Roberts, on vanity labels with names like Ef-N-De, Norva and Guide.

His store was situated near one of the chapels owned by Bishop Daddy Grace, a legendary preacher who, before his death in 1960, had amassed a nationwide 350-temple franchise. His church’s rhythmic New Orleans-derived music was the heartbeat for the black community in Norfolk—and it came courtesy of the Griffin Brothers and their legendary drummer, Emmett “Nabs” Shields, who had contributed the backbeat on Barge’s “Country” 45.

In late 1959, Guida purchased the Norfolk Recording Studio, on Princess Anne Road, for $1,757. Perhaps the budding producer’s most important hire was the experienced Gene Barge. “Guida knew that I had gone to New York to play with Ertegun, and he used to always say, ‘I bet they didn’t treat you right, blah blah blah … . Why don’t you come along with me?’”

In picking the players for the Church Street Five studio band, Barge and Guida chose many of those responsible for the rousing sound that resonated around Daddy Grace’s church. “Guida knew some of the guys. We both agreed on Nabs Shields, who was the best drummer around anyway. We had a guy named Junior Fairley, who was a great bass player that had played with the Griffin Brothers. We might’ve had Willie Burnell on piano. We had a trombonist named Leonard Barks—he was the one that played the ‘Quarter to Three’ riff.” Guida said that Barks was added to the Church Street Five because he “wanted that Daddy Grace House of Prayer sound.”

Originally, Barge was signed as a solo artist. “When I came in, I did a couple of vocals, and then they decided, ‘Let’s do this instrumental.’ And we were talking about Daddy Grace’s church. So Guida came up with the idea: ‘Why don’t we call the song, “A Nite with Daddy G.”’” The long jam was split into two parts on the single and released under the Church Street Five name.

Guida’s burgeoning Legrand label had already scored a big national hit with “New Orleans,” by Gary U.S. Bonds. “I had nothing to do with ‘New Orleans,’” Barge says. “Earl Swanson played the solo and did the session.” But he knew the singer well—as little Gary Anderson. “Gary was just a kid in the neighborhood. I used to see him out [in Norfolk] with his mother. He had a pretty mother. And his father was a Navy man. And I used to see him out there when he was 5 and 6 years old. I didn’t even know Gary could sing, period, until he came out with ‘New Orleans.’”

Barge’s honking, rollicking “A Nite with Daddy G” didn’t do much on the pop charts for Legrand. But it was adopted as a theme song by the influential Philadelphia DJ, Hy Litt, and gave the saxophonist his lasting nickname. “No one really knew I was doing a takeoff on a church thing, they just thought I was talking about myself. And that’s how I became Daddy G. So we did some followups, but Guida was more concerned with trying to get Gary going again after ‘New Orleans.’”

After Bonds failed to follow up on his hit, he put a melody and lyrics to “A Nite with Daddy G.” The result was an unlikely #1 smash, “Quarter to Three.” Barge remembers that it was initially a non-starter. “What happened on ‘Quarter to Three’ was, when they started mailing it to jocks, they wouldn’t play it. They said, ‘This sounds like it was cut in the crapper.’”

This wasn’t far from the truth—the vocal tracks at Guida’s studio were recorded in the bathroom. At the same time, the music’s bass-heavy beat was ready-made for dancing. Infectious and fun, it was still the most “lo-fi” record to ever make it to number one. Upon proclaiming it one of the 1001 Greatest Singles of All Time in his book of the same name, critic Dave Marsh wrote of “Quarter to Three,” “[It] has the most peculiar unity. I’ve played it on stereo systems ranging in price from $49.95 to $10,000, and the equipment makes no difference.”

At the time, Guida instructed Bonds to tell Dick Clark on American Bandstand that his songs were recorded live. “But they weren’t,” Guida said in 2000. “They were all electronically created.” To add weight to a track, Guida and engineer Joe Royster—a shoe salesman by day—would bring in neighborhood kids, overdub their claps and murmurs and create a party. “The recording started to sound crappy after four or five generations [of overdubs],” he said. “But you could still hear the bass drum coming through.”

Barge believes that something else helped the sound. “Gary has a talent to be able to overdub himself. He can sing exactly the same rendition … he could sing “Quarter to Three” and then go back and sing another version exactly the same, with the same inflections. A lot of people can’t do that. They forgot what they did. He must have multi’d that about seven times—ping-ponging and overdubbing. Give Joe Royster the credit there. Joe Royster made it happen. It was like five or six Garys on that record.”

Music fans in Great Britain were particularly fascinated by this new, primal roar, so different from the sedate fare of the teen idols (Fabian, Frankie Avalon) then in vogue. Distributed in the U.K. on EMI’s Top Rank label and, later, on Stateside, “Quarter to Three” was the source of much discussion in the British trade papers. “This record is fuzzy, muzzy and distorted,” Jack Good wrote of “Quarter to Three” in a 1961 column for Disc magazine. “According to present-day technical standards it is appalling. However, for my money, the disc is not just good, it’s sensational and revolutionary.

“[‘Quarter to Three’] introduces a new era of pop recording. Realism and surrealism is old hat. Impressionism is the thing. ‘Quarter to Three’ is clearly not interested in reproducing the sounds of a band and a voice, of a group chanting and clapping in the background. These things are only useful as a canvas upon which an impression can be painted of the changing textures of sound itself … the thickness of it, the muffled reverberations, the vibrant roughness of it.”

In the pounding echoes of “Quarter to Three,” Good heard a coming age of studio manipulation in rock ‘n’ roll music. “This is a whole new sound world,” he wrote. “And the possibilities for development are endless and fascinating.”

At first, Barge says, no one wanted it. “There was a little promotion man—can’t think of his name. Not highly regarded. He tells Guida, ‘Man, look, gimme that record, I’ll get it played.’ So, [Guida] thinking he’d go to Washington, D.C., or Philadelphia, he went way back in the woods to these small radio stations where guys owed him favors, and these guys started playing it. And lo and behold, people started calling in for the record. And it started that way. … There was a buzz [started] about ‘Quarter to Three.’

“This happened eventually … weeks later, man.” He laughs. “It’s all about marketing and promotion, I don’t care who you are. If you can’t get it to the people, you don’t exist. If the public don’t hear it, there’s no sales, no action.”

“Quarter to Three” was definitely heard. It invited a host of immediate sound-alikes (Guida: “You don’t have to be a genius to listen to ‘Runaround Sue’ and hear ‘Quarter to Three’”) and shoutouts (the Dovells would salute Daddy G on the popular “Bristol Stomp”). One barely solvent outfit in the U.K., called the Silver Beatles, fresh from dabbling in skiffle and busy brewing up what would become the British Invasion, included “Norfolk Sound” hits in their early sets. Years later, John Lennon would buy a jukebox and stock it with the songs that meant the most to him. Among the platters were Gary U.S. Bonds’ “New Orleans” and “Quarter to Three.”

Back home in the U.S., emerging Northwest rockers The Kingsmen and Paul Revere & the Raiders honed their riffing skills playing the same party songs. In New Jersey, Bruce Springsteen was another wide-eyed lad slavering over Bonds and the Church Street Five 45s in the early ’60s. The future bandleader would later enlist a saxophone player schooled in the sweaty sax work of Barge and Swanson—Clarence Clemons, of Chesapeake, Virginia—to be his E-Street outfit’s “Daddy G.” Springsteen repaid the favor of the influence by masterminding Bonds’ career revival in the early ’80s.

“I could never capitalize on that record, nor the fame of it,” Barge says today. “Gary was a young guy, so he never would push the ‘Daddy G’ end of it. As far as he was concerned, I was just a sideman, In fact, I didn’t even go out on tour with Gary. I was teaching school anyway.”

Throughout his musical endeavors, Barge kept his day job—teaching English, social studies and music to students at East Suffolk High. He remembers his days as the coolest teacher in school as being hard (“all those papers I had to grade”) but rewarding. “I got some of the students who wouldn’t behave themselves to listen to me, [the ones] that the other teachers couldn’t do anything with. A couple of guys who were failing became B+ students. Before, they weren’t doing their homework, not paying attention. I could see that they had intelligence and the wherewithal to be better students.”

The saxophonist’s connection to East Suffolk explains the host of school-themed songs he wrote with Bonds in the early ’60s—the top 10 hit, “School Is Out,” its less-popular (go figure) followup, “School Is In,” “Mixed Up Faculty” and “Too Much Homework.” He laughs. “Yeah, that was me, coming up with ideas in the high school environment.” For his part, Bonds (who still performs) speaks of Barge as a mentor—he even lived with the sax player during his early hitmaking days, after the saxophonist separated from his first wife, Mildred.

For years, Daddy G was reluctant to talk about the pioneering work he did in Norfolk—he believes he is owed numerous royalties from TV and movie licensing, and memories of working with Guida still cause discomfort. “You’d have Guida standing in the middle of the floor, humming crazy stuff. We were rejecting half of it—‘That ain’t going to fly, man. C’mon.’ We would argue. Sometimes he would stop the session and sit down to lecture us about what he knew and didn’t know. And we’d have to listen to him. We knew Guida was a jerk, you know. We had been knowing it.”

The producer maintained, in 2000, that he imposed the jaunty calypso melodies he’d learned while stationed in Trinidad during World War II on his blues and gospel-based performers. “You have to understand that when I worked with these musicians, all of them were deeply steeped in the old rhythm and blues progressions, changes and so on,” Guida said. “That’s why I have such a strong objection to [these songs] being classified as R&B.” When it came to Barge, he said, “I had to pound the changes into his head.”

After playing a memorable sax solo on another #1 Guida-produced record, Jimmy Soul’s “If You Wanna Be Happy,” Barge had had enough. 1964 was his final year at East Suffolk, and he was being hounded by the IRS for back taxes on song royalties. He had just married his second wife, Sarah, a bank teller from Newport News, and she agreed with him: It was time to go. “I called Phil Chess at Chess Records and asked him if he had a job for me. He said it wouldn’t pay much, but yeah, he had something.”

It’s worth noting that Frank Guida and his Norfolk song factory never hit the top 10 again after Gene Barge moved to the Windy City.

“I think I left Norfolk on a Saturday and I went to work in Chicago on Monday.”

Working full-time in music for the first time in his life, Barge’s first sessions in Chicago, for brothers Phil and Leonard Chess, led to a classic. “When I got there, [bandleader] Oliver Sain had Fontella Bass singing a song called ‘Soul of a Man’ with his band. When Phil heard Fontella sing, he asked me to get my sax. Even though Oliver Sain was a noted sax player in St. Louis, they asked me to play … . That song made a little noise on the rhythm and blues charts and, some kind of way, they got her to sign a single artist contract, got her away from Oliver, and she ends up recording ‘Rescue Me.’ I played with the horn section [on that]. We’re getting—musicians are still getting paid for a commercial running now that uses part of the song. They are wearing it out on television.”

According to Nadine Cohodas’ excellent book on Chess, Spinning Blues Into Gold, Barge arrived at an opportune time. The blues-based label was expanding into jazz and gospel and trying to get a handle on soul music in the wake of Motown’s success. This created a need for competent arrangers and session musicians.

Along with Fontella Bass, “Little Milton was one of the first artists I worked with. We came up with this song, ‘We’re Gonna Make It’… and it took off for him.” He also blew solos and/or arranged for Chess artists Bo Diddley, Etta James, Andre Williams, the Dells, Sugar Pie DeSanto and Little Walter. After a time, he was put in charge of the label’s religious roster, overseeing the Soul Stirrers and other groups. “I just have a feel for the gospel music,” he says. “My first public appearance was in church, back when I was playing clarinet. I’ve always been close to gospel.”

In his off hours, he would perform with a local blues guitarist. “Buddy Guy asked me to play in his band and I played with him throughout the Chicago area. He was unknown around the country, but not around Chicago. Willie Dixon wanted me to help him with Koko Taylor. He had brought her in from the South, and I ended up playing with Buddy on ‘Wang Dang Doodle,’ her first big single. We started gigging around locally, so I talked Chess into signing him and I recorded his album, Left My Blues in San Francisco.”

He gave breaks to other emerging talents while at Chess. “Donny Hathaway was multi-talented, a great pianist. When I first met him, he was looking for a job. He said, ‘I’m tired of working with Curtis Mayfield and I need something.’ We carried him upstairs to see what he could do and sat him down in front of a grand piano. We hired him on the spot, convinced Chess to hire him as a staff producer.” Hathaway, who suffered from schizophrenia and would die tragically in 1979, wasn’t hampered by his illness at that point, Barge says. “He was a little strange, but that doesn’t mean he was mental. He was all music, as far as I could see.”

Another talented performer, also cut down in the prime of life, got her start with Barge. “Minnie Ripperton was a girl stopping by Chess every day on her way back from high school. She sung background on nearly everything I did there, for just about all of the artists on Chess—even ‘Here Come The Judge,’ by Pigmeat Markham. She was great, everyone loved Minnie. She was like my little daughter.”

In 1965, at age 39, the perennial sideman got the opportunity to cut his first solo disc. Dance with Daddy G was Chess’ attempt to cash in on the sax player’s “party” rep from “Quarter to Three”—a honkin’ instrumental ride featuring a mix of covers (the Beatles’ “I Feel Fine,” the Isley Brothers’ “Shake”) and originals (“Voice Your Choice”). Barge doesn’t recall it fondly. “It’s OK. We did all of this stuff in a hurry. In the middle-’60s, all of these dances hit the streets: the Monkey, the Jerk, Chubby had done the Twist. It was our attempt at that.”

These initial years in Chicago were fruitful. “They weren’t like Guida, but they were tough,” he says of the Chess brothers. “You couldn’t pull nothing over on them. They started in the nightclub business.” Barge believes that, like a lot of the old independent labels, Chess “cheated on a lot of guys for royalties. They had strange bookkeeping.” To make up for the low wages, Barge would often “go down the street” to lend his saxophone to sessions for artists on other labels, such as Jackie Wilson and the Chi-Lites. You can hear him on Wilson’s top 10 hit “Higher and Higher,” for instance.

As the end of the ’60s approached, he participated in two of the most notorious projects in blues history—albums by Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf that attempted to cash in on heavy psychedelic rock music. “Electric Mud was one of Muddy’s biggest sellers. But Howlin’ Wolf didn’t like it, didn’t want to do it. He would cuss and fuss the whole time. He questioned the fact that we were taking him out of his orbit. He was a traditional Arkansas boy, with traditional music, and here we are. And he was concerned about whether he could do it or not. We told him, ‘Regardless of all this stuff, don’t change your style. We’ll just drop this stuff in all around you.’”

By the time Leonard Chess died in 1969, the record label was sold and its artist roster was dwindling. Barge soon went to work for another seminal American imprint, Stax, handling their gospel artists. “But I didn’t last long there, because they were having their problems too.” He stayed in Chicago and became a sought-after arranger, producer and session musician—including chart-topping work with a young Natalie Cole.

But he would tackle other challenges, like starring in an independent movie, shot in Chicago, called Stony Island. Fledgling director Andrew Davis discovered that the former schoolteacher, while not a trained actor, was a natural fit to portray a music mentor who assists a young soul band in making it to the big time. “Working with young musicians was right in my line of work,” Barge says. “Andy was one of those brats who came through the Chicago public school. We had a lot in common and hit it off.”

Davis would eventually become an A-list Hollywood director, specializing in action films such as The Fugitive and Chain Reaction. He’s cast his good friend Gene Barge in most of his movies since Stony Island, giving the novice actor the chance to exchange lines with the likes of Gene Hackman (“exceptionally nice”), Harrison Ford (“almost like a loner—he didn’t do a lot of socializing”), Tommy Lee Jones (“Tommy Lee is cool”) and Morgan Freeman (“very smart guy, he likes to talk”). Acting is only a hobby, although he notes that the music and movie businesses share similarities. “They are both heartbreakers. Success in either is a matter of breaks and a matter of luck,” he says.

In 1976, the same year he won a Grammy for co-producing Natalie Cole’s “Sophisticated Lady,” he made a new, important friend. “Ahmet Ertegun called me and said, ‘I’m coming into Chicago to cut [singer] Willie Mabon and a couple more guys,’ and he wanted me to recommend a studio and also to call the musicians for the session. So I did all that. He called me before [the date], he said, ‘I’m bringing Mick Jagger with me. He wants to just hang out.’”

“He and Mick stayed a week, and that’s how I got to know Jagger, from that. He was helping Ertegun put this [Atlantic records] session together. He’s a nice guy. We struck up a little friendship that week in the studio.” The meeting led to Daddy G being asked to perform, years later, on the 1982 Rolling Stones European Tour. “I played with them the whole summer,” he remembers. “It was probably the greatest gig I ever had. We played soccer stadiums—holding 60, 65 thousand people. Wembley Stadium was 70 thousand. We played one date at Leeds that held 100,000.”

He didn’t witness much wild tour debauchery. “They were over that, although Keith Richard is always on the verge of doing something. Thing is, their reputation precedes them.” He says that when the Stones tour landed in Sweden, for instance, the band and entourage were strip-searched. “Everyone was clean, but as soon as we got through, Keith pulls out a joint. I don’t know where he was hiding it.”

“Gene Barge is the flyest octogenarian I know,“ says Public Enemy’s Chuck D. “To go from Muddy Waters to Public Enemy is a good trick.”

He’s on the phone from New York City, singing the virtues of the veteran musician who will make another appearance on one of his band’s hard-hitting rap albums. “He’s legendary, as far as I’m concerned.” Last year, Barge performed a solo on P.E.’s “Superman’s Black in the Building,” and the next is due next year.

“I don’t know how good a job I did,” Daddy G says of the sessions. “I wasn’t all that pleased with what I did. If he’s happy with it, I’m thrilled,” Barge says, admitting that “there haven’t been many things lately that I’m happy with that I’ve done, solo-wise. A lot of the times, the record producers want a solo, and there are already tracks laid down and you don’t have time to live with it, and they are going ‘great, great …,’ but you don’t think it’s so great.”

He was recently in the studio with soul legend Otis Clay. “I played a solo on that one. I wasn’t thrilled with that either,” he laughs. “No, really, the only session stuff I’m doing right now is for my own label [Thisit] and the gospel stuff we’re doing.”

With organic instruments like his saxophone losing ground to the synthesizer, he laments the rise of computer technology in making today’s music—“the soul is missing”—but he yearns to keep up. “Like it or not, that’s how the music is made today. I’m getting a laptop,” he insists. “I’m computer-illiterate, but I’m going to work on it.” One of his two children, daughter Gina, is a freelance writer and consultant who lives near her parents. “She’s going to help me.”

Even with his long studio resume, Gene Barge’s passion is still performing live, these days as a leader of the Chicago Rhythm & Blues Kings, formerly Big Twist & the Mellow Fellows. In September 2006, the musician came back home with the Kings to the place where he grew up and got his first horn, to play a pair of gigs—one in J.M. Randall’s excellent Williamsburg club, the other at the annual Blues at the Beach festival in Virginia Beach.

In the Kings’ show, the 80-year-old sideman takes over the spotlight for half of the sets, showcasing the latest of his late-blossoming talents: Lead vocalist and frontman. Watching him alternate between sax playing and his forceful sing-song delivery—stepping, swaying, honking—you’d swear you were watching a man 30 years younger, not a senior citizen who suffers from emphysema. Chuck D is right: This is one damn cool 80-year-old man, one who is determined not to live in the past.

“I feel like I ain’t there yet. I’m sitting here looking at my horn now, feeling guilty because I didn’t get enough practice time in today—I’m mad because I didn’t write a song, or the intro to a song. I got things to do. I’m not looking back,” he says. “My philosophy is that you’ve got to move forward, stay contemporary, read, keep up with the young people. Because that’s the future.”

– Originally published February 2007