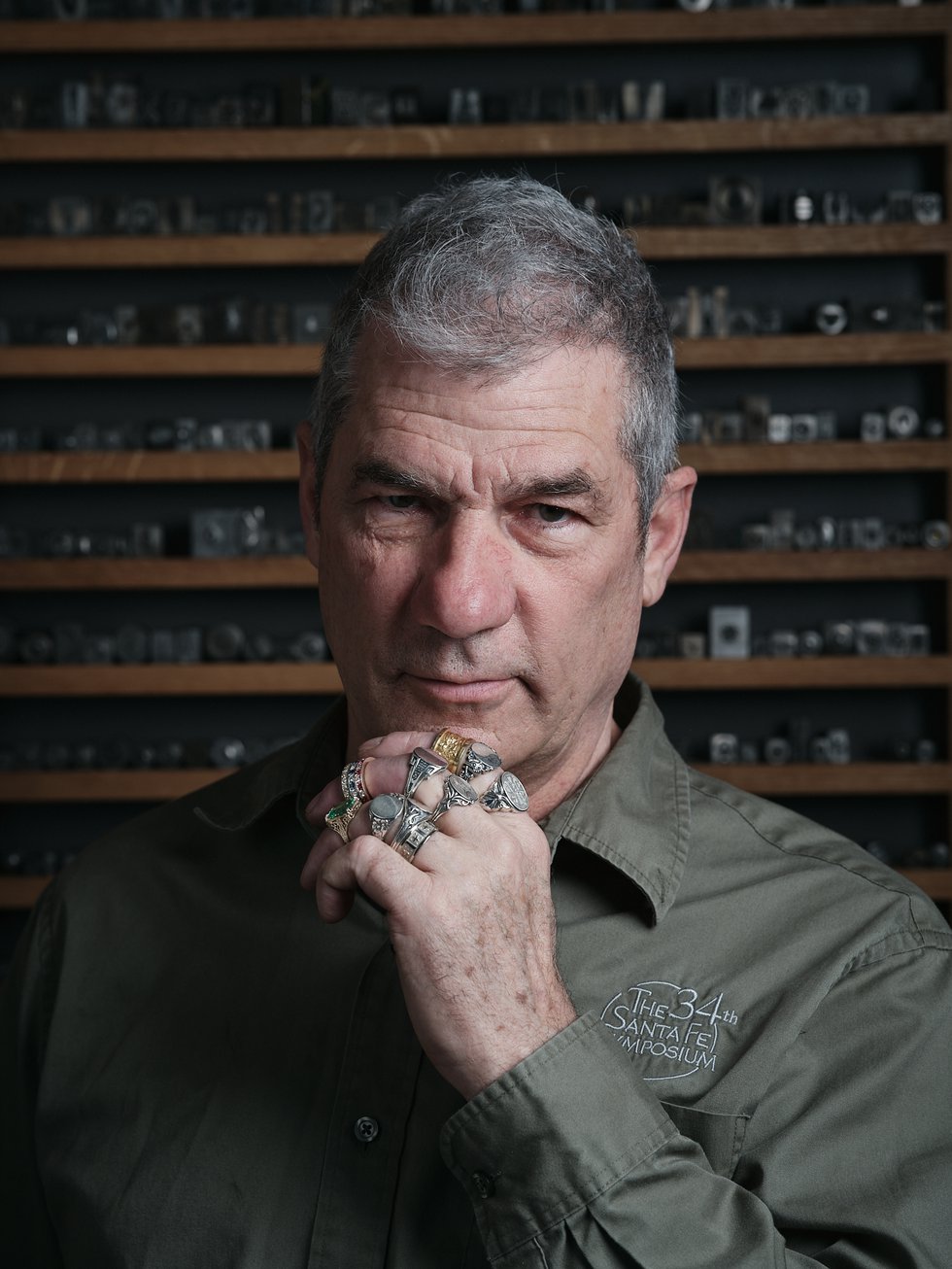

Entering Hugo Kohl’s boutique shop, what’s immediately eye-catching are the fine and elegant earrings, pendants, and rings, all crafted on site, many of which are true to American historical periods. Kohl made his reputation on vintage filigree designs that he, unlike many others, was able to make cost effectively. His location—in Harrisonburg’s renovated and hip Ice House complex—is a perfect setting for a man who’s fascinated by human industry and our evolving relationships with machines.

If you want a deep dive into this cherished craft, show up for a studio tour on Thursdays at 2 p.m. You’ll feel like you stepped into a wing of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, and after Kohl’s tour, you may not see jewelry and its production quite the same. In fact, the proud James Madison University graduate does refer to this busy workshop—with its walls of historic hubs (aka steel jewelry molds) and an impressive array of industrial machines—as the Museum of American Jewelry Design and Manufacturing.

In 1993, through a right-place-right-time bit of luck and his own initiative, Kohl came to possess a box of antique jewelry hubs with gorgeous, intricate designs. He’d made a pilgrimage to the shipping town of Provincetown, Rhode Island, to track down what was left of this Industrial Age jewelry-making center that thrived from the 1790s through mid-1970s. He ended up rescuing many of its remnants from the junkyard or those bound for metal scrapping. Some—both the hubs and early machines—he and his trained staff put back to work, while others he mainly admires. For his tours, he’s welcomed everyone from kindergartners to industrial design students.

Kohl’s respect for well-designed tools resonates throughout his workshop. One machine is an 1830s screw press, which was “integral to the Industrial Age and the workhorse of the jewelry-making industry,” he says. That device and others, like a drop hammer, were created mainly to multiply the physical power of the humans who ran them. One of Kohl’s aesthetic prizes is an ornate mid-1800s scale that was used to measure gold in Philadelphia—in the days when U.S. dollars had to be backed by precise weights in precious metals. In addition to being well-designed and ultra-precise, this scale also represents “how this country was starting to become the gigantic manufacturing powerhouse in the world,” he explains.

Kohl also freely shares his thoughts on the social importance of American jewelry’s history. “Mechanical mass production made jewelry affordable for everyone,” he points out. While different social classes may have bought jewelry made with different metals (brass and copper items for the poorer folk, and gold and platinum for the wealthy), they were usually buying the same designs made from the same hubs and even perhaps from the very machines that Kohl resuscitated.

Over the years and post-pandemic, this workshop has become a jewelry-making playground for Kohl, who crafts pieces that manifest his customer’s wishes—but also his own. While he walks his dog, Dorian Gray, a whippet, Rhodesian ridgeback, and black lab mix, his eye is often inspired by items from nature, like a shapely leaf or a cicada wing that he’ll work into a piece. Selling it or not selling it is not really the point. He also experiments with some out-of-the-box designs, including placing gemstones on jewelry in unexpected places or at unusual angles. These machines and his own expertise enable him to craft “at the edge of what the laws of physics can be.”

Lately, Kohl challenges his own skills by embellishing wedding bands with metal engravings that symbolically circumnavigate the band without end. “People really enjoy that,” he says, and also that his well-made items can be handed down through generations. His pieces range from $125 to $10,000—for a specially requested design.

“I get to create things out of my imagination with my hands, and I have every possible goldsmithing tool ever invented, from 200 years ago till now,” Kohl says. “For me, it’s kind of like dying and going to heaven.”