Burke’s Garden, in southwestern Virginia, pop. 300, lies in a beautiful, isolated, high-altitude valley with no post office, cell phone service or cable, and a harsh climate. As one resident says, “Something unpredictable could happen at any time.”

A thistle, left, and Marvin Meek.

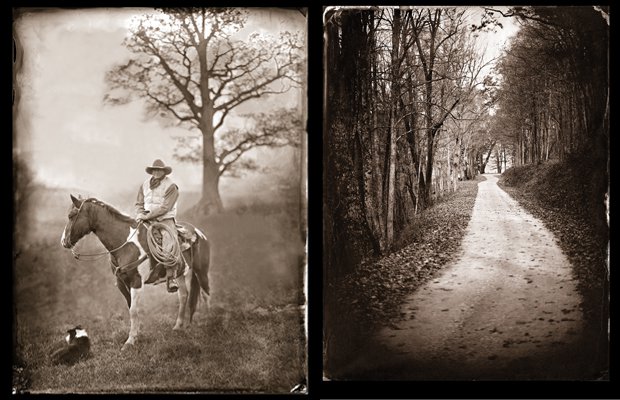

John Rhudy, and a road out of Burke’s Garden.

Signs for various spots, and Burke’s Garden church.

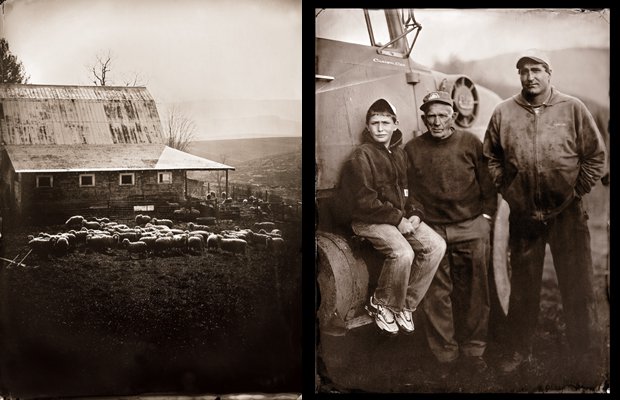

Charlotte Whitted’s sheep, left, and three generations of the Snapp family, on their dairy farm.

Rick Snapp

The old post office, now defunct, and Shelby Jewel, a member of the Bluegrass Kinsmen.

An aerial view of Burke’s Garden.

Charlotte Whitted lets her children, and her sheep, roam free in the summertime. John Rhudy rides horses, like a cowboy, to round up cattle across hundreds of acres of grassland. White-haired Marvin Meek recalls tales of Tazewell County and how the residents of his unincorporated hometown banded together in 1940, at the onset of World War II, to stop a sheep-killing bear they called “Old Hitler” because he was so beastly.

These characters—and roughly 300 others—live in the fabled and topographically unique agricultural community in rural southwestern Virginia named Burke’s Garden. Unique because “the Garden,” as Burke’s Garden native Kent Hoge and other residents call it, is a high and hidden valley, a bowl situated at an average elevation of 3,100 feet and surrounded by Garden Mountain, a circle-shaped rise in Tazewell County’s southeastern corner. Viewed from above, via aerial photographs, Burke’s Garden looks like a verdant crater—as if a mischievous giant, eons ago, had pressed his thumb into the cone of a volcano.

One thing is certain: Burke’s Garden is a beautiful land that, to a certain degree, time forgot. The place is completely off the grid of modern life: There is no newspaper delivery in the town, and no cable television; no stoplights and no working post office. And no cell phone service. Many of the residents are retired, a few of them farm, and lots drive out to work in nearby towns, constantly challenged by often-sketchy road conditions leading in and out of Burke’s Garden. Says the 39-year-old Rhudy, a graduate of Tazewell High School and Radford University, “Unless you’ve grown up here and really like the rural setting, it’s a different world.”

Owing to its remote, relatively high-altitude location, Burke’s Garden is largely defined by its isolation and its weather, which is usually either cool or teeth-chattering cold. The average annual temperature is about 50 degrees, and in spring and summer—when the grasslands ripen and bald eagles begin to patrol the picturesque, lake-size pond of the Gose Mill—the mercury rarely exceeds 80 degrees. Unlike most places in Virginia, or the mid-Atlantic for that matter, Burke’s Garden gets a fairly significant amount of snow in the winter, sometimes several feet a year, which blocks roads and exacerbates the place’s lonely beauty.

There is just one paved road between Burke’s Garden and the nearest town, Tazewell, 30 minutes away. Another road, made of gravel, winds down the backside of Burke’s Garden, crossing the Appalachian Trail en route to Bland County. It is strictly off-limits in the winter. One additional route—what 75-year-old dairy farmer Rich Snapp calls “the CCC Road” (built in the 1930s by the Civilian Conservation Corps)—stays so rough that it’s best traveled only in a Jeep to reach the tiny village of Bastian, a dozen miles away.

The locals are not only used to the sometimes harsh climate, they like it. Ruth Snapp, the 74-year-old wife of Rich Snapp, savors the winter: “I don’t mind being housed-up. I do a lot of quilting.”

Charlotte Whitted, who is executive director of the Historic Crab Orchard Museum and Pioneer Park in Tazewell, agrees. “Part of the lure of living in Burke’s Garden is that something unpredictable could happen at any time, and the weather is a piece of that. You just never know what you’re getting. There’s always a tale down at the general store of somebody’s chicken house that blew away or somebody’s roof blowing off.”

Rhudy, the cowboy, says there was a week or more this past February when the snow was so high, “it was not worth the effort to get out.”

Rick Snapp, 32, is a son of Rich and Ruth Snapp and was born in nearby Bluefield, W.Va., yet he claims, proudly, to be a lifelong resident of Burke’s Garden. Rick grew up in his parents’ early-20th-century farmhouse. The Snapp family has farmed this land since the days of the Civil War, says Rick. His father and grandfather worked the land and the barns, and so does he. The family now owns 223 acres of land, producing milk on their dairy farm. They also lease another 1,000 acres to raise beef cattle and hay. It’s tough work, says Rick, who works extra jobs like clearing local driveways in winter for commuters (one of whom is his wife, Selena)—but he is fond of the rural lifestyle. “Any kid growing up in the country has an advantage over kids growing up in the city,” he asserts. Rick wants his children, ages 10 and 14, to be farmers, too.

Will they? Even in a slow-moving place like this, the fabric of life is gradually changing. Time was, the residents stayed put for weeks—or even months—at a time. “I never got to town much when I was a little boy,” says 76-year-old J.L. Rhudy Jr., a lifelong resident, farmer and a cousin to John Rhudy. “I never knew where town was.”

Indeed, in the immediate post-war decades, Burke’s Garden was a self-supporting community with its own post office, high school and a larger population. “You had general stores here, you know, where you bought your stuff,” says 70-year-old Kent Hoge, a retired farmer. The local school brimmed with children. “Your schoolteachers, you knew them, and they knew you,” Hoge says. “And a lot of them, they grew up here in the Garden, or they married into the Garden. And there was about only one person that drove out of here every day.”

That’s not the case now. For one thing, fewer people in the valley are farming. That shift has got the locals driving a lot more, to jobs outside the area. The old Burke’s Garden school building sits vacant, used only occasionally as a community center. It was the victim of school consolidation, a move that required Garden students to be bused over the mountain to Tazewell.

“The big land holdings are all being broken up,” says Bill Jurgelski, a doctor and New Jersey native who, at age 79, works as many as a dozen shifts a month as a part-time emergency room doctor in the nearby Richlands and Grundy hospitals. He moved to the Garden in 1998. “Most of the current generation is not interested in farming,” he says, “so they are selling off their land.”

Marvin Meek, 88, affirms this. “Farming is a lost thing. Land prices have gotten so high, you can’t make it work. Now, young kids have to go find a job doing something that’s better than farming.”

Until the 1980s, hardly any property was sold. “It used to be said that the only way you could get a place in Burke’s Garden was you had to inherit it or marry it,” says Meek. “That was pretty much true. But it isn’t anymore.” Born to a farming family in Burke’s Garden in 1922, the spirited Meek moved west, to Arizona, in 1942 and eventually worked for actor John Wayne on the movie star’s 26 Bar Ranch. Meek returned to the Garden in 1986 and now spends his days making furniture, such as pie safes, and caring for his ailing wife, the former Ella Baumgardner. He also remembers Wayne: “He was a nice guy and a true American.”

How was Burke’s Garden formed? There are more than a few theories about its geological origins. Meek thinks the valley was once a lake, while Rich Snapp offers another idea: “Some say a meteor hit it and flattened it out.” Still others suggest the area was once part of a volcano. Geologists get the last word, and they’ve apparently said, according to Tazewell historian and author Louise Leslie, that this bowl was once a 6,500-foot-high mountain largely composed of limestone, but with a sandstone cap. Slowly, that sandstone cap eroded, and the peak of Garden Mountain collapsed into itself. That’s the “common wisdom,” says Whitted. “And the limestone shifts all the time, so that’s a pretty believable story.”

James Burk, a hunter who spelled his last name without an “e,” is credited in history books with discovering this place. As Tazewell County legend has it, Burk chased a wounded elk into the valley in the 1740s, then, after setting up camp, he buried the peelings of his potatoes so Indians could not track him. Explorers later found that Burk’s peelings had grown into a potato garden and, as a joke, they named the area “Burk’s Garden.” The name stuck. Centuries later, the valley is still fertile, Whitted says. “I’ve just found that it doesn’t take hardly any effort at all to get things to grow.”

Whatever the origin of its topography and name, the Garden has a powerful effect on some residents. Jurgelski named his farm the “Lost World Ranch” to reflect both the remoteness of the area and the herd of 40 Bactrian camels he raises. Jurgelski has owned the camels, two-hump camels native to Mongolia, for 14 years, since before moving to Burke’s Garden. “I’ve just gotten attached to them,” he says.

Whitted, as part of her job at the Historic Crab Orchard Museum, enjoys telling Garden tales (tall or otherwise) herself. Standing in the museum, she points to a stuffed carcass known as the Varmint—it’s actually a coyote—and says that in 1953 the animal killed more than 400 of Burke’s Garden’s sheep, eluding capture for nearly a year before it was finally shot to death by a professional hunter.

What’s the big deal about shooting a coyote? In Whitted’s view, the Varmint saga symbolizes the spirit of Burke’s Garden. “These are people who can take care of themselves,” she says.

Like Jurgelski, Whitted is a transplant. In 1999, she and her husband, Gordon, a schoolteacher, were living in Lawsonville, N.C., but were searching for a farm to raise both their sheep and their family. When they saw the area, the couple, now in their 40s, were smitten. “If you drive over the mountain, you realize, ‘Well, yeah, this is it,’” Whitted says. “I thought it was obvious. The land is fabulous, beautiful; in many ways, it’s got some idyllic qualities. And it’s a great place to raise children,” even if that means spending a lot of time in the car, driving the kids back and forth to school in Tazewell every day.

Libby Bowman, who has lived here since 1962, welcomes newcomers, inviting them to join the Burke’s Garden Homemakers Club, an organization that occasionally publishes community cookbooks. She worries, however, that the population is becoming more seasonal. “We are getting more people who are building houses here and living here part-time,” she says. “We really preferred when they lived here all the time and [we] knew who they were.”

For a few years, in the 1990s, a few Amish families lived in Burke’s Garden. They operated their own store, school and factory, making wooden railings for fences and porches. “They were good, hard-working people,” John Rhudy says, and they believed in helping their community. But they eventually left, he says, because they were unable to buy enough land for their children to live in the area.

Being “neighborly” is, of course, an essential component of the rural ethic. Waving her arm to encompass the residents, Whitted says, “These are [people] whom you call when your barn is burning down or you’ve thrown your tractor in the creek, and you’ve got to have somebody pull you out.”

When the summer arrives, Burke’s Garden families will begin to till their fertile soil—and do it quickly, facing one of the shortest growing seasons in the state. With little humidity, there’s virtually no need for air-conditioning. Breezes steadily waft through the open windows of century-old farmhouses. “There’s the smell of good hay being put up,” Rick Snapp says, smiling, “and you watch the corn grow.”

Warm weather brings a few visitors, mainly bird-watchers and bikers tracing the scenic byways. Jurgelski, at the Lost World Ranch, gives people rides on his camels. He can foresee how road improvements might change Burke’s Garden permanently, making it a retirement colony or “just a regular village.”

The old ways and means could wane, but for now the community remains “close-knit,” says Meek. “We haven’t changed a lot in the last hundred years.” He and others are happy to live out their retirement in the splendid quiet that is Burke’s Garden. “We’re not trying to beat the next guy,” Meek says. “It’s just a good place to kind of let down.”